On Thursday, a symposium through the journalism program:

Corruption: Who Plays? Who Pays?- Thursday, April 16, 2015 4:00 pm Paul Brest Hall East

Homework

Some bot code

RaiseNotBeg bot on Github - Politely tells people they are using "begs the question incorrectly".

@RaiseNotBeg you're a dumb garbage bot and i hope your owner feels bad about making you.

— ya boi james colley (@JamColley) April 15, 2015HotStories bot on Github - A sinmpler bot, broken down into four steps:

- Collecting tweets

- Deciding which tweet is worth rewteeting

- Sending the actual tweet

And then there's the "scheduler" script which wraps all the other three steps and runs them in a constant loop.

Thinking in loops

Another domain, but same concept: Programmer Mary Rose Cook live-codes a JavaScript game. You can see the annotated source code here.

It's a great demonstration of how a website – and game – can be built from an empty text file. And it's a great demonstration of the basic logic behind every game: a dumb loop that runs for as long as the program is on, and on each run, it checks to see which "bullets" have to move, where the player is, and then draws all the pixels on the screen:

// Main game tick function. Loops forever, running 60ish times a second.

var tick = function() {

// Update game state.

self.update();

// Draw game bodies.

self.draw(screen, gameSize);

// Queue up the next call to tick with the browser.

requestAnimationFrame(tick);

};

// Run the first game tick. All future calls will be scheduled by

// the tick() function itself.

tick();

};

Mary live-codes a JavaScript game from scratch – Mary Rose Cook at Front-Trends 2014 from Front-Trends on Vimeo.

Bots and Notifications

This week we're going to conflate a few concepts:

- Bots: programs that are given a task and are then left unsupervised or partially supervised to do that task until the end of time or their computer's power suppply.

- Notifications: Messages, mostly of the push variety, telling a subscribed audience, "you need to know this."

It's possible to have bots that don't send notifications. And it's possible to have notifications that aren't sent by bots. However, it's an interesting programming challenge to combine both concepts in a way that doesn't annoy the hell out of people while doing something useful.

Things to do

- By Wednesday: Make a new Twitter account to send tweets from…this way you don't pollute your personal account. The easiest way to do this is, if you have GMail, to register with an email address of:

yournormalname+mytwitterbot@gmail.com…GMail will redirect all of these emails toyournormalname@gmail.comwhile other services will treat is as a unique email. This is handy for handing out email addresses that can be easily filtered. - Optional: Sign up for Mandrill and test sending emails via Python

- Optional: Sign up for Twilio and test sending text messages via Python

My Bible-word-tweeting bot

Some draft code here on Github. Probably shouldn't consider it an example of a best practice.

Behold ABISHUR and its 2 Biblical appearances!

👼🙏😇

BibleHub: http://t.co/19hMBHugbH

Wikipedia: http://t.co/Yrtjy7cFCZ

— Behold Every Word (@beholdeveryword) April 13, 2015Why notifications

Notifications are necessary in our digital life because who can remember to check websites/newspapers every day on a routine basis? And sometimes there's information that just needs to be pushed at us, to guarantee that we get it.

As I've said before, filtering is the most fundamental task in journalism and computing and pretty much all of design. Getting notifications right requires:

- Knowing what is worth being notified about.

- How to prevent too many notifications.

- How to prevent irrelevant notifications.

- How to prevent redundant notifications.

These are very hard things to figure out even on paper, never mind programmatically.

Bad notifications

It's best to start off with how well-intended notifications can go wrong:

Amber Alerts in New York City: Children are important. Protecting them is important. So what could go wrong with having all smartphones receive text messages whenever a child is in danger?

- Does it make sense to alert 8+ million people every time a child is believed to be abducted?

- Why send alerts for abductions and not other life-threatening events?

- Can the alerts be narrowed to NY residents who are in that vicinity and still awake?

- Can that narrowing be done without the use of statewide surveillance of phones?

- If the alert was simply put up on a webpage, i.e. a passive notification, who would bother to check it?

The Amber Alert as implemented by default in NY was very annoying, to the point where people probably just turned it off. On the other hand, there is no easy solution to that problem.

Facebook email notifications

If you don't go on Facebook for awhile, you'll be getting emails like this:

Why is the fact that one of my friends (and how does Facebook pick one out of hundreds/thousands to spotlight?) getting a few comments on his/her post merit an email alert?

NYT App Notifications

Yes, The Times and Journal Are Sending You More Push Notifications

This Just In: Behind the News Alert

Recently we debated whether to alert Dave Itzkoff’s exclusive that Trevor Noah would be the new host of “The Daily Show.” We knew there would be a lot of interest, but we weren’t sure if naming the new host of a television program met our bar for breaking news. We decided it didn’t; instead we tweeted a headline, posted our article to Facebook and put it in a prominent position on our home page. That one could have gone either way.

Disagreements often arise around the deaths of prominent figures or celebrities. Some are easy (Nelson Mandela, Robin Williams), but others are on the bubble. When the musician Joe Cocker died in December, there was much back and forth between the News Desk and the Culture Desk. The debate ranged from “He’s a legend!” “He was at Woodstock!” to “He was just a hippie!” and “Who’s he?” In this case, Mr. Cocker prevailed.

Wrestling with these trickier calls has evolved into a parlor game of sorts. I’ll hear a song on the radio or watch an old movie and think, Would I send an alert on that guy?

Axl Rose? Of course. Slash? Maybe. Duff McKagan? Probably not.

Why bots?

Think of bots as actors in an automation strategy, tireless workers who can deal with the most tedious of information work without complaint. A programmer sets up some rules/filters – such as, check to see if Wikpedia has been edited by an IP address that comes from Congress. Usually, but not necessarily always, the bot is then given a task/subroutine to perform when its rules/filters have been set off, such as, "send out a Tweet".

So as you come up with your own bot, think of these two primary and separate things:

- What is interesting for a bot to automatically check on?

- What should the bot do when it finds something?

Number 1 is generally the hardest thing to do. Whereas #2 is pretty straightforward and requires looking up available services, such as (as of 2015), Mandrill for emailing, Twilio for texting/calling, and Twitter, for, well, TWitter.

Human intervention is OK

The trick is to not think that everything has to be done by the program. For example, the Times Haiku Bot is tasked to programmatically read New York Times articles and, with the use of an electronic dictionary, determines the syllables for each word – though some are added manually, such as "Rihanna".

In the end, human editors decide what gets published to the Haiku Tumblr:

Not every haiku our computer finds is a good one. The algorithm discards some potential poems if they are awkwardly constructed and it does not scan articles covering sensitive topics. Furthermore, the machine has no aesthetic sense. It can't distinguish between an elegant verse and a plodding one. But, when it does stumble across something beautiful or funny or just a gem of a haiku, human journalists select it and post it on this blog.

Sample haiku:

Darius Kazemi and his bots

Boston Globe: The botmaker who sees through the Internet - "Darius Kazemi’s little creations are funny, poignant, popular—and a sly commentary on how the Web is organizing our lives"

How to make a Twitter bot by Darius Kazemi:

…there are really two pieces to the process of making a Twitter bot: the Twitter piece, and the bot piece.

If you want to make a creative, interesting bot, you need to understand computer programming. Seriously. You don’t have to be a good programmer, but at the most basic level you need to be able to read API documentation, search for stuff on StackOverflow, copy/paste/modify that code into your own, debug error messages from servers, and run things on the command line.

Github repository for examplebot (using NodeJS): dariusk/examplebot

How I built Metaphor-a-Minute (Github source)

Bot Examples

A bunch of examples here.

Wikipedia-related bots

The Shadowy World of Wikipedia's Editing Bots

Wikipedia Is Edited by Bots. That’s a Good Thing.

Wikipedia:List of bots by number of edits

Here's a time when Wikipedia bots were fooled by a human (and human-processes): Jared Owens, God of Wikipedia:

On May 29, 2005, an anonymous editor using an Australian IP address added “Jar’Edo Wens” (an exotically punctuated “Jared Owens”) to Wikipedia’s Australian Aboriginal mythology article. Ten minutes later, the same editor created a brief article for Jar’Edo Wens: “In Australian Aboriginal mythology, Jar’Edo Wens is a god of earthly knowledge and physical might, created by Altjira to oversee that the people did not get too big-headed, associated with victory and intelligence.”

To ensure that there was no doubt that this was someone having a little Internet fun, rather than a serious attempt to catalog obscure Aboriginal deities, the same editor also added your mom (“Yohrmum”) to the list of Aboriginal mythological figures.

…Then came the parade of bots. Bots adding “orphan” tags. Bots requesting more references. Bots pointlessly changing the capitalization of the markup and adding sort keys to ensure the article would be sorted by “Jar” and not “Wens” in the category views. Bots changing the types of maintenance templates and moving whitespace around. It wasn’t until November 2014 that an anonymous editor suspected something was up, and tagged the article as a possible hoax. Three months later, it was finally nominated for deletion.

…The altruistic instinct that compels us to pick up a piece of litter in our path is equally powerful in compelling well-meaning WikiGnomes to “improve” content by adding links and categories. (I know: I do it myself.) But in the case of subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) vandalism and hoaxes, the effect is nonetheless to put lipstick on a pig, or, as Dilbert’s Scott Adams often puts it, to “polish a turd.” There is, in fact, a great deal of turd-polishing done on Wikipedia, for well-intentioned reasons: Wikipedia channels the innate human desire to improve things, but can do so in a way that produces absurd, if not harmful, results.

congress-edits

Jimmy Duncan (U.S. politician) Wikipedia article edited anonymously from US House of Representatives http://t.co/jnKpyxYTGj

— congress-edits (@congressedits) April 9, 2015On Twitter: @congressedits and @parliamentedits

On Github: edsu/anon

Earthquake bots

The LA Times Quakebot

A sample LA Times Quakebot story:

An example of a program demanding human attention isKen Schwenke's Quakebot, which, upon receiving an earthquake alert via the USGS email feed, parses it, writes a half-decent story with the relevant facts (the time, the magnitude, the closest cities to the epicenter), then sends it along to the Los Angeles Times newsdesk, which then has to confirm the details, make tweaks to the copy, and then push the publish button. The first Quakebot story (at least that Schwencke publicly revealed) was eight minutes after seismographs first started trembling.

Quakebot obviously saves its creator a lot of time – that's why Schwencke titled his essay about Quakebot, "How to break news while you sleep". However, Schwencke had to do all of the decision-making, including deciding when an earthquake is important enough for Quakebot to take action.

Earthquakesla

Someone apparently unaffiliated with the LA Times has tackled the same issue except instead of publishing stories, their bot tweets the important details (and a link to an interactive map):

On Twitter: @earthquakesla

1.5 mag earthquake occurred 0.62mi SSW of View Park-Windsor Hills, California. Details: http://t.co/Yrzh5rUlnm Map: http://t.co/Zhsg2nZmMg

— LA QuakeBot (@earthquakesLA) April 13, 2015The Australian shark bot

On Twitter: @slswa

More Than 300 Sharks In Australia Are Now On Twitter

Government researchers have tagged 338 sharks with acoustic transmitters that monitor where the animals are. When a tagged shark is about half a mile away from a beach, it triggers a computer alert, which tweets out a message on the Surf Life Saving Western Australia Twitter feed. The tweet notes the shark's size, breed and approximate location.

SCOTUS-SERVO

On Github: vzvenyach/scotus-servo

On Twitter: [@SCOTUS_servo](https://twitter.com/SCOTUS_servo

POSSIBLE CHANGE ALERT in Kansas v. Nebraska (before https://t.co/V3ktSs728n & after http://t.co/RUlTtRR1Nz)

— SCOTUS Servo (@SCOTUS_servo) April 3, 2015Clever piece of code exposes hidden changes to Supreme Court opinions

Supreme Court opinions are the law of the land, and so it’s a problem when the Justices change the words of the decisions without telling anyone. This happens on a regular basis, but fortunately a lawyer in Washington appears to have just found a solution.

The issue, as Adam Liptak explained in the New York Times, is that original statements by the Justices about everything from EPA policy to American Jewish communities, are disappearing from decisions — and being replaced by new language that says something entirely different. As you can imagine, this is a problem for lawyers, scholars, journalists and everyone else who relies on Supreme Court opinions.

Until now, the only way to detect when a decision has been altered is a painstaking comparison of earlier and later copies — provided, of course, that someone knew a decision had been changed in the first place. Thanks to a simple Twitter tool, the process may become much easier.

David Zvenyach is general counsel to the Council of the District of Columbia and, in his spare time, likes to experiment with computer code. Upon learning of Liptak’s column, which was based on a study by Harvard law professor Richard Lazurus, he decided to so something about it.

Last week, he launched @Scotus_servo, a Twitter account that alerts followers whenever a change is made to a Supreme Court opinion.

The process is fairly simple. As Zvenyach explained in a phone interview, it uses Node, an application written in JavaScript, to crawl the “slip” opinions posted to the Supreme Court website. If the application, which performs a crawl every five minutes, detects a change, it notifies the automated Twitter account, which tweets out an alert.

Shortly after, Zvenyach sends out a manual tweet that calls attention to the change — something he has already had to do, flagging a small change to a patent opinion this month:

Patent lawyers & bluebook fans. SCOTUS updated its cite in Nautilus:

Orig: https://t.co/jyopsY3Von

New: https://t.co/kTqyCM1DsD

(p 9)

— SCOTUS Servo (@SCOTUS_servo) June 9, 2014Nailbiter bot

On Twitter: @Nailbiterbot

M: Duke (1) v. Wisconsin (1) is 61-58 with 2:48 left. Watch on CBS. http://t.co/WpPBV9f2uH

— Nailbiter Bot (@NailbiterBot) April 7, 2015Via WNYC Data News team:

Last year, the day before the first full round of the NCAA basketball tournament, WNYC reporter Jim O'Grady mentioned that with 32 games in two days, he had trouble keeping tabs on all the action. He wished for a way to get a text message when a game was going down to the wire so he’d know to drop everything, neglect his professional duties, and tune in. With that conversation, @NailbiterBot was born.

This year, we’re bringing back Nailbiter Bot for both the men’s and women’s tournaments. The premise is simple: the account will tweet whenever a men’s or women’s tournament game is close near the end. A game counts as close if:

The score is within 8 points with between 1:30 and 3:00 left on the clock

The score is within 6 points with between :30 and 1:30 left on the clock

The score is within 4 points in the last 30 seconds

The @everyword bot

On Twitter: @everyword

zwieback

— everyword (@everyword) June 6, 2014One Man's Quest to Tweet Every Word in the English Language

Since late 2007, an obscure Twitter account has been automatically tweeting a single word every half an hour. The ultimate goal: to tweet every word in the English language. We spoke to the guy behind Everyword.

Parrish set up a Python script that runs every half hour and tweets the next word on an alphabetical list of 109,229 words. Obviously, this is not every word in the English language—a number that is impossible to pin down. It's not even every word in most dictionaries. (The Oxford English Dictionary has more than 170,000 words.) Annoyed Twitter have pointed this out, but Parrish says that's part of the point.

Times Haiku

Not an April Fool’s joke: The New York Times has built a haiku bot

Times Haiku is a collection of what they are calling “serendipitous poetry,” derived from stories that have made the homepage of NYTimes.com. The haiku live on a Tumblr hosted by the Times. Harris built a script that mines stories for haiku-friendly words and then reassembles them into poetry. (For those of you that may have zoned out in class, haiku are comprised of three lines with, in order, five, seven, and five syllables.) The code checks words against an open source pronunciation dictionary, which handily also contains syllable counts.

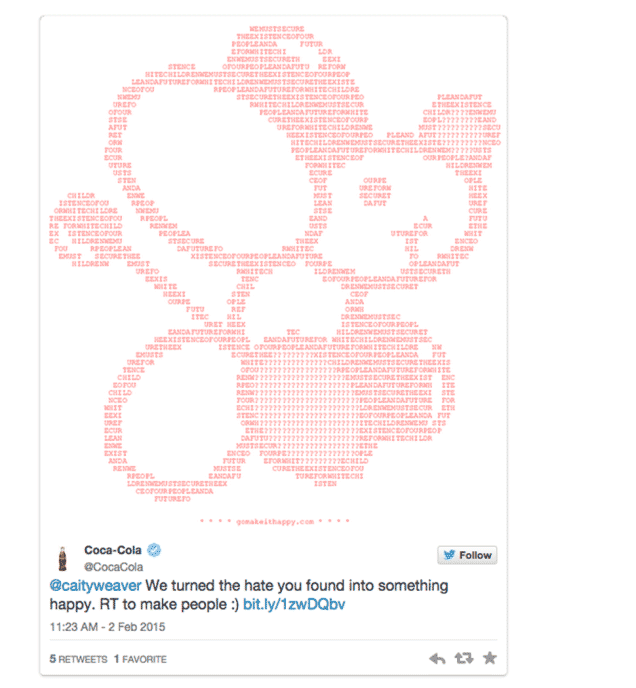

Coca-Cola's Hitler-Quoting Bot

One of the many examples of: just because you automate it doesn't mean you should. Or: Bots are as dumb as their humans. The Coca-Cola #MakeItHappy bot, which transformed negative tweets into "cute ASCII Art", undoubtedly had some filters to prevent profanity from appearing. But what if the tweets contained non-profane words? Such as: "We must secure the existence of our people and a future for White Children."

via Gawker:

Make Hitler Happy: The Beginning of Mein Kampf, as Told by Coca-Cola