- Todos

- Some notes for 2015-04-29

- Notes for 2015-04-27

- Simplifying the questions we ask

- Bot detection

- Apgar Score

Todos

-

Check the todos

- New homework: USAJobs Midterm Part 1

- Answers posted to Dicts, Lists, and JSON Quiz Part 1 and Sorting fun with JSON Quiz Part 2

- Twitter Bot stuff we'll revisit next week, but please make sure you can at least send a tweet from within Python:

Some notes for 2015-04-29

Cool visualization via Quartz on Nepal Earthquakes

via Allison McCann at 538: Where Your State Gets Its Money (fivethirtyeight.com)

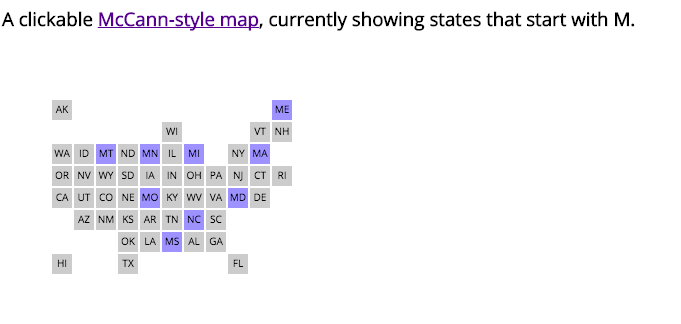

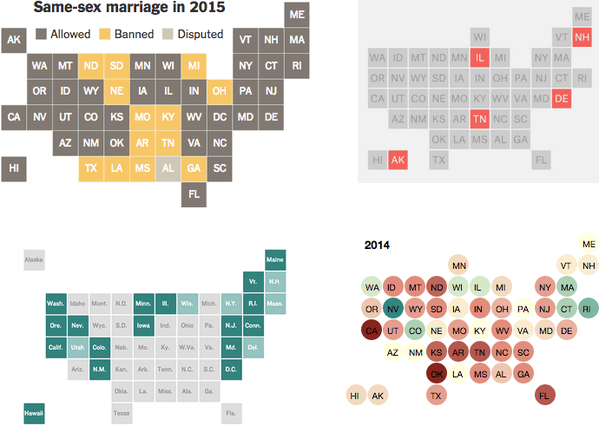

A version of that graphic in JS/HTML: https://gist.github.com/yanofsky/917dd6a532cc4fa3808a

More examples from Quartz's Yanofsky

Free dinner tonight

Sponsored by Stanford Journalism:

Burt Herman will be talking at the Stanford Daily on Wednesday, April 29 at 6pm, with a Tacolicious dinner to follow at 7pm. He will be talking about his career in journalism, his work at Storify, and the rewards of digital storytelling. More on Burt, a Stanford alum and former JSK Fellow, at http://www.burtherman.com/

Explore APIs on your own

There will be at least two more sections to the midterm. But otherwise, we've covered what I think you need to know to be effective, if not elegant, because when you can tell a computer to do something, brute force is not a bad strategy.

So there won't be any more exercises to see if you can tell apart what's a list and what's a dictionary, or how to get JSON into those data structures. It's up to you to test out what seemingly-little you know (downloading a file and having access to its contents is a huge step) using what you find in the real-world.

Search-Script-Scrape

Remember that Search-Script-Scrape exercise? I'm still expecting you to do it. Believe it or not, if you can even attempt the first part of the midterm, you know more than enough programming logic to complete SSS. What you currently lack, though, is, how to deal with things that aren't necessarily JSON (such as HTML or CSV). Those two data formats have their own libraries, which we can figure out in time. But the end process is the same:

- You download text from a URL (requests will pretty much always work)

- You parse the text with the proper tool (e.g.

json.loads()) and turn it into a Python list or dictionary - You extract what you want from that list or dictionary.

Go through the SSS exercises and in your own version of the spreadsheet, at least mark down which of the problems involve JSON. A lot of the motivation behind SSS was to acquaint you with real-world datasets, in advance of your final project for this class.

Other APIs to explore

Well, for starters: How to Auto-Grade People on Github. (You might want to run the is_passing() function on your own account…)

Notes for 2015-04-27

Example of Twitter bot-rating code

As shown in class:

Simple Metrics for Detecting Twitter Bots

Simplifying the questions we ask

Being that computers are ultimately limited to processing 1s and 0s, they are profoundly awkward in answering non-binary (i.e. yes/no, true/false) questions, e.g. "What is love?", or yes/no questions that are based off of nuanced observations, e.g. "Does this person love me?"

So there are basically two approaches:

1. Increase the sophistication of the models and queries

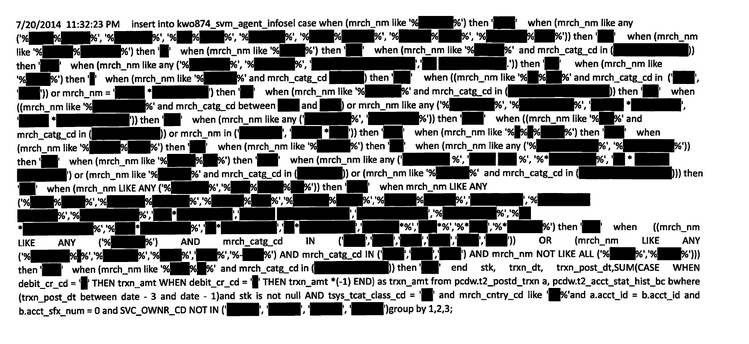

An example can be found in this recent article about "How PayPal beats the bad guys". Or in allegations that Capital One fraud detection analysts committed insider trading when they searched credit-card usage data to divine that Capital One customers were increasingly going to Chipotle.

(actually we don't know if their calculations were that complicated, just that the redacted SQL query is pretty gruesome:)

2. Simplify your criteria

It's possible that networked computing power in the future will be so fast that it can give satisfactory answers to complicated questions. But until then, why not go for a mostly-good, 80%-of-the-way solution?

A great journalistic example: determining the America's "worst charity" using a single number: the amount of money "blown on soliciting costs", e.g. the ratio of total money raised by solicitors versus paid to solicitors. Both of those are a simple data point that can be culled from 990s.

Countless babies' lives were born simply because a doctor came up with a system to add points for every easily observable vital sign (Apgar's Score) - no fancy technology needed.

Look at dating

Pre-2012, dating websites were heavily into algorithms:

Who's Telling You the Truth About Dating Algorithms?

The online dating industry is a $4 billion business. And everyone from popular author Dr. Pepper Schwartz to mathletic OkCupid cofounder Sam Yagan is trying to crack the code for success. Business success.

Looking for Someone - Sex, love, and loneliness on the Internet.

In 2005, in response to the success of eHarmony, Match.com began developing a new site—a longer-term-relationship operation with a scientific underpinning. The white coat whom Match.com recruited for this new counter-venture was a biological anthropologist named Helen Fisher, a research professor at Rutgers and a renowned scholar of human attraction and attachment. Fisher’s observations and findings regarding the human personality, romantic or otherwise, are rooted in her study of the human species over the millennia and in the role that brain chemistry plays in temperament, especially with regard to love, attraction, choice, and compatibility.

On OkCupid:

OK Cupid sends all your answers to its servers, which are housed on Broad Street in New York. The algorithms find the people out there whose answers best correspond to yours—how yours fit their desires and how theirs meet yours, and according to what degree of importance. It’s a Venn diagram. And then the algorithms determine how exceptional those particular correlations are: it’s more statistically significant to share an affection for the Willies than for the Beatles. The match is expressed as a percentage. Each match search requires tens of millions of mathematical operations. To the extent that OK Cupid has any abiding faith, it is in mathematics.

Then Tinder came along; Love Me Tinder:

Tinder does not give out statistics about the number of its users, but the app has grown from being the plaything of a few hundred Los Angeles party kids to a multinational phenomenon in less than a year. Unlike the robot yentas of yore (Match.com, OkCupid, eHarmony), which out-competed one another with claims of compatibility algorithms and secret love formulas, the only promise Tinder makes is to show you the other users in your immediate vicinity. Depending on your feelings for these people, you swipe them to the left (meaning “no thanks”) or to the right (“yes, please”). Two people who swipe each other to the right will “match.” Your matches accrue in a folder, and often that's the end of the story. Other times you start texting. The swiping phase is as lulling in its eye-glazing repetition as a casino slot machine, the chatting phase ideal for idle, noncommittal flirting. In terms of popularity, Tinder is a massive and undeniable success. Whether it works depends on your idea of “working.”

Bot detection

Read The Bot Bubble: How Click Farms Have Inflated Social Media Currency by the New Republic'sDoug Bock Clark.

Questions to answer:

- What are the basic steps used by botmakers to avoid spam detection?

- Why is it so difficult to stop spammers?

- Technical issues aside, and cynically speaking, why would Facebook and other social networks not do more to prevent spammers.

- Technical issues aside, why would social networks want to root out spammers?

- Come up with 5 metrics not listed in the article to block spammers that are reasonable to implement.

Related:

- 7 Habits of Highly Fraudulent Users via Sift Science.

- Social Media Bots Offer Phony Friends and Real Profit via the New York Times.

- Hacker News discussion on New Republic article

- []()

Apgar Score

via Atul Gawande of the New Yorker:

But the situation wasn’t so encouraging for newborns: one in thirty still died at birth—odds that were scarcely better than those of the century before—and it wasn’t clear how that could be changed. Then a doctor named Virginia Apgar, who was working in New York, had an idea. It was a ridiculously simple idea, but it transformed obstetrics and the nature of childbirth. Apgar was an unlikely revolutionary for obstetrics. For starters, she had never delivered a baby—not as a doctor and not even as a mother.

The Apgar score, as it became known universally, allowed nurses to rate the condition of babies at birth on a scale from zero to ten. An infant got two points if it was pink all over, two for crying, two for taking good, vigorous breaths, two for moving all four limbs, and two if its heart rate was over a hundred. Ten points meant a child born in perfect condition. Four points or less meant a blue, limp baby.

The score was published in 1953, and it transformed child delivery. It turned an intangible and impressionistic clinical concept—the condition of a newly born baby—into a number that people could collect and compare. Using it required observation and documentation of the true condition of every baby. Moreover, even if only because doctors are competitive, it drove them to want to produce better scores—and therefore better outcomes—for the newborns they delivered.

The Wikipedia entry for the Apgar score:

Virginia Apgar invented the Apgar score in 1952 as a method to quickly summarize the health of newborn children. Apgar was an anesthesiologist who developed the score in order to ascertain the effects of obstetric anesthesia on babies.

A summary of the metric via the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, particularly its limitations, and to warn against it "being used inappropriately in term infants to predict specific neurologic outcome":

It is important to recognize the limitations of the Apgar score. The Apgar score is an expression of the infant's physiologic condition, has a limited time frame, and includes subjective components. In addition, the biochemical disturbance must be significant before the score is affected. Elements of the score such as tone, color, and reflex irritability partially depend on the physiologic maturity of the infant. The healthy preterm infant with no evidence of asphyxia may receive a low score only because of immaturity (6). A number of factors may influence an Apgar score, including but not limited to drugs, trauma, congenital anomalies, infections, hypoxia, hypovolemia, and preterm birth (7). The incidence of low Apgar scores is inversely related to birth weight, and a low score is limited in predicting morbidity or mortality (8). Accordingly, it is inappropriate to use an Apgar score alone to establish the diagnosis of asphyxia.

ACOG notes that it's not just the score itself that is important, but when it is taken (when the baby is 1- and 5-minutes old), and the difference between the two measurements. Also, the score's relevancy has not been tested in situations in which the baby is undergoing resuscitation.

NIH definition of the APGAR test

Random notes

Peter Norvig (director of research at Google) wrote a Python solution for the When is Cheryl's Birthday logic puzzle. It's a perfect example of how a programming solution is typically much longer and convoluted than the pen-and-pencil solution. Nonetheless, it demonstrates how logical principles can be stated as programmatic functions, so it's a nice demonstration for all the times when abstracting a problem is the right path.

Review the USAJobs site and API

(old)

There will be a homework/"midterm" of sorts, based off of the data found at USAJobs.gov. I'll have it in by Tuesday (yes, I know, I said that last week; and it will be due over the next week).

For now, do yourself a favor and visit the USAJobs.gov homepage:

Then do a search by location for "France":

/Search?Keyword=&Location=France&search=Search&AutoCompleteSelected=true

Then meander on over to the homepage for the REST API of data.usajobs.gov. In particular, read the API Query Parameters Tab.

Then visit this sample URL in your web browser (your browser will either show plaintext, or might downlaod the file (as plain text) to your Downloads folder):

https://data.usajobs.gov/api/jobs?Country=France

And then try this snippet of Python code in iPython:

import requests

url = "https://data.usajobs.gov/api/jobs?Country=France"

data = requests.get(url).json()

print('There are %s job openings' % data['TotalJobs'])

for job in data['JobData']:

print("%s, for the %s, with a max salary of %s" % (job['JobTitle'], job['OrganizationName'], job['SalaryMax']))

Then you've got the gist of what the homework entails.